Eliud Kipchoge: “Accept no limits”

Kipchoge’s mental outlook seems even more important than his physical gifts

By Amby Burfoot

Eliud Kipchoge, red shirt at right. Kaptagat, Kenya 2005.

(Photo by Mary Austin.)

A number of years ago, while running with Eliud Kipchoge--yes, I did actually run with Kipchoge--I asked him an simple question. His answer reflects probably the most important aspect of his unprecedented marathon career.

You have heard by now that Kipchoge ran a 2:01:09 marathon Sunday in Berlin to break his own marathon world record. You know that he has won the last two Olympic gold medals in the marathon. You know that he ran a mindblowing 1:59:40.2 in the INEOS exhibition marathon in Zurich three years ago.

I could go on, but there would be no point. At this stage, anything anyone writes about Kipchoge’s marathons is essentially pointless. We simply don’t have the words. Nor do his “stats” make any sense. He’s on a different planet than any previous marathon runner, thus comparison is empty.

So I return to my easy training run with Kipchoge. It took place in early 2005, high on the Rift Valley escarpment near Kaptagat, Kenya. I was there with a small group of American marathon fans eager to learn more about the Kenyan runners. The tour was led by John Manners, himself a seasoned track and field aficionado. Manners grew up partially in Kenya, learned Swahili, went to Harvard, and had a long journalism career at the old Time-Life. He provided deep research for several of Kenny Moore’s wonderful Sports Illustrated articles about Kenyan runners.

With this background, Manners was able to secure our group a run and meeting with the Kaptagat training camp runners. We assembled on one of Kenya’s famously red and rutted clay roads.

Before we set out, I stepped forward rather timidly to make a request. “My wife wants to run 4 miles today, but she’s not very fast,” I said to the Kenyans. “Would anyone be willing to run 10-minute pace with us?”

You understand, of course, that these were mostly guys who could race 10,000 meters on the track at 4:30 pace. I didn’t expect a response from any of them.

One raised his hand, however, and stepped forward from behind the others. He had a wide, disarming smile. Yes, you guessed it.

As the other runners, Kenyans and awestruck Americans, moved steadily ahead of us on the clay road, Eliud Kipchoge hung back. My wife was huffing and puffing, but I had the chance to ask him several questions as we ran.

Even before that, I marveled that he had acquiesced to our slow pace. I didn’t know any elite Westerners who would have agreed to the same. They would have considered it a waste of time and effort, if not worse. After all, you don’t advance your world-class status by slogging along with hobby joggers.

Eighteen months earlier, at the 2003 World Championships, Kipchoge had won the 5000 meters in 12:52.79 over the seriously fast Hicham El Guerrouj and Kenenisa Bekele. I had always considered Ethiopians better kickers than Kenyan distance aces, based mainly on the results of Miruts “Yifter the Shifter” Yifter and Haile Gebrsellassie.

So I decided to question Kipchoge about this. “When you’re racing the Ethiopians on the track, don’t you worry that they will outkick you?” I asked.

“No I don’t fear the Ethiopians,” Kipchoge replied. “I don’t feel fear about anything.”

That was 17 years ago. Kipchoge’s marathon prove that his attitude, perhaps more than anything else, has helped him separate from the pack. He often says, “No human is limited,” and he’s been running that way for decades. The mind is more important than the legs.

Eliud Kipchoge, red shirt standing, Katagat, 2005. (Photo by Mary Austin.)

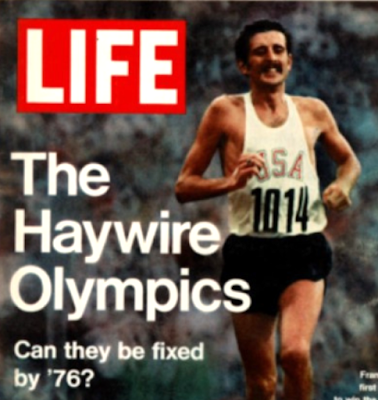

50 Years after Munich: What Frank Shorter Means to Running

But I don’t remember and revere Shorter for his gold medal as much as for the words he spoke to Kenny Moore about why they should run in Munich. The Marathon took place just 5 days after the massacre of Israeli Olympic athletes. “We have to not let this detract from our performance,” Shorter said. “Because that’s what they want.”

These words reflect and reinforce the healing power of running. We have needed similar words on too many occasions since Munich--at the 2001 NYC Marathon post 9-11; when Ryan Shay died in the 2008 Olympic Marathon Trials; during and after Hurricane Sandy and its devastating impact on New York City and its canceled marathon; and in our return to running events after Covid.

And especially, particularly, most emotionally of all, in our reclaimiing of the 2014 Boston Marathon after the bombings, deaths, and maimings of 2013. We humans face frighteningly random and uncontrollable events, from the immense natural forces around us, and too often from ourselves. (I’m thinking at this moment of the tragic murder of Eliza Fletcher in Memphis.)

And yet we struggle back. We remain resilient. We return to running.

Because it is all we can do. And everything we must do. In 1972, Frank Shorter gave us the performance and words that still set the standard: “We have to not let this detract ….”

That’s why I’ll be remembering and honoring Shorter on Saturday--50 years after the Munich Olympics but as relevant as ever.